Posts in Category: 18th century

Hacking Historical Maps… or trying to

This weekend, I spent Sunday afternoon experimenting with solutions for historical mapping with Mia Ridge, a digital humanist and doyenne of hack days. We staged our own mini hack day to work through some of the challenges involved with the mapping side of my project on Parisian parishes, a major component of which involves geolocating demographic data to map the neighbourhoods in which artists lived in 18th-century Paris.

Over the past few years I’ve done the archival digging to come up with the data and now I’m at the stage of looking for the best ways to visualise it, both for research purposes (i.e. for me to use while thinking through and writing up the results) and for publication (i.e. how do you get copyright to publish a map in a book or journal article when you’ve built it on a commercial service like Google Maps?). Today we were mainly focusing on the first problem as it seemed the easier of the two, but ideally there’ll be a single solution for both.

I experimented with two websites, Georeferencer and Hypercities, both of which I’ve used in the past, but today I was hoping to explore some more of their features. In the end, however, while both have some useful functionalities, neither was perfectly suited to my requirements (though it must be said that Hypercities seemed to have a bug that was preventing data from being saved so it was difficult to explore far). As you can see from the screenshot of my results with Georeferencer, I successfully georeferenced a fragment of an 18th-century map on Google Maps… but there was no way to geolocate historical data on it.

Mia experimented with Metacarter and Mapwarper, and has written up her results and experiences over at Open Objects. I have a major problem with sites like Metacarter because everything you produce is publicly visible, which obviously makes it very difficult when you’re working with unpublished data. Most sites allow the option of keeping the maps you make restricted and that makes more sense for academics using these sites for research purposes. I’m excited to share my research when it’s complete, but I’d like to have control over what happens in the meantime.

| Administrative map of Paris, 1890 (Uni of Chicago Library) |

So all-in-all I didn’t discover the ideal open-access resource in a single afternoon (shock-horror) and for now I’ll just have to keep going with the methods I’ve been using. But I have been able to pinpoint more accurately what it is that I’m looking for and what challenges I face in finding it. And as a happy bi-product we also discovered lots of wonderful sites providing access to historical maps that I hadn’t encountered before, like the David Rumsey Map Collection and a great collection of 19th-century maps of Paris at the University of Chicago Library (most in high resolution with zoomify for getting into the detail of street level, as you can see in the screenshot).

Artists’ Things on the road

Katie Scott and I have been taking Artists’ Things out and about with two presentations already this year and another booked in. Our formula for these dual presentations seems to be working quite well – the feedback so far has been great and we’ve had some dynamic discussions and really useful leads. Each paper begins with one of us giving an introduction with a conceptual frame that sets up the themes that will emerge from the interventions to come – then we each take one object from our collection and present them in dialogue, one after the other.

For the CRASSH ’18th Century Things’ series in Cambridge, we explored the materiality of artistic practice through two professional tools – Fragonard’s colour box and Houdon’s modelling stand, and for AAH2012 at the Open University we looked at everyday life in the French Royal Academy through two institutional objects – the secretary’s document box and the concierge’s register of funeral invitations. The next stop for us is going to be Lyon for the Luxury and Trade Conference this November, where we will be talking about (you guessed it) artists’ luxury possessions. Through Boucher’s shell collection and Coypel’s gold watch, instead of the more conventional image of the artist as a producer of luxury goods, we will explore the artist’s role as a consumer.

If you’re interested, you can listen to our CRASSH presentation in the 18th Century Things audio archive, where you’ll also find lots of other stimulating papers on 18th-century ‘stuff’. Abstracts for the papers can be found on the Artists’ Things website.

Why do we care about Molière’s armchair?

With a couple of hours to spare in Paris on a research trip last month, I went to Comédie Française s’expose at the Petit Palais. The exhibition recounts the history of the Comédie Française through its visual and material remains, tracing the life of the company from its beginnings under Molière in the 17th-century to its revered state today. All is presented through a chronological arrangement of objects including props and costumes; set designs (a whole room of them); theatre buildings; a manuscript ledger – Extraict des Receptes et des affaires de la Comédie depuis de l’année 1659 – recording the daily business of the company; and a jeton probably used as a voting token in company meetings. There were also many portraits of Comédie Française actors and playwrights forming a who’s who of French theatre through the ages.

Perhaps the most direct (and certainly the most poignant) connection to the company’s past was to be found in the personal objects that once belonged to the company’s founder. One of the first rooms in the exhibition was devoted to Molière – with low lighting and spotlit displays, the experience here was of a sacred space dedicated to this patron (and the mostly French exhibition goers were indeed observing appropriately hushed tones). Along with his effigy in a series of portraits and the company ledger open to the page recording his death, there was a trio of reliquaries (seen in my blurry photo): his armchair (first used in the production of the Malade Imaginaire in 1673 and later as a seat in Company meetings), his watch, and his bonnet.

Perhaps the most direct (and certainly the most poignant) connection to the company’s past was to be found in the personal objects that once belonged to the company’s founder. One of the first rooms in the exhibition was devoted to Molière – with low lighting and spotlit displays, the experience here was of a sacred space dedicated to this patron (and the mostly French exhibition goers were indeed observing appropriately hushed tones). Along with his effigy in a series of portraits and the company ledger open to the page recording his death, there was a trio of reliquaries (seen in my blurry photo): his armchair (first used in the production of the Malade Imaginaire in 1673 and later as a seat in Company meetings), his watch, and his bonnet.

Being in Paris on the hunt for artists’ things for the Artists’ Things project (see earlier post) and having spent days scouring museums and archives for the merest material trace of 18th-century artists, I was particularly struck by the survival of so many of the 17th-century playwright’s possessions. Molière as an individual reached an iconic status that no single 18th-century French artist did, but nevertheless, I found myself wondering why there is comparatively much more interest in collecting, preserving and revering the things that once belonged to writers than those that belonged to artists. Indeed, a large-scale replica of Molière’s armchair once became a piece of public sculpture outside the Théâtre de la Comédie Française, and Voltaire’s personally customised armchair is on permanent display at the Musée Carnavalet. In the context of museum display, maybe writers’ personal objects are more visually engaging than a page of manuscript, or maybe it’s just a French thing about armchairs.

As we’re discovering, 18th-century artists’ things do survive (armchairs among them), but they’re usually lying forgotten in museum store rooms or in the corner of a room. Obviously art works make for much more visually exciting encounters in museums than tatty old domestic objects, but wouldn’t people want to see, for instance, the brush that created the canvas? Is Shakespeare’s quill really more exciting than Michelangelo’s chisel? It left me thinking about how personal possessions survive in the first place, and what role the cult of personality plays in preservation and display.

Lemoyne’s Suicide again

I’m presenting my research on François Lemoyne’s suicide for the Edgar Wind Society in Oxford this week. I think their event poster has definitely captured the spirit of the thing!

For more on the Edgar Wind Society, you can find information about previous and upcoming events on their website.

New Ways through Old Maps: Artistic Communities in 18th-Century Paris

As part of my research on 18th-century French religious art, I’ve been doing significant archival work on artists and parish life in Paris. A large part of this involves finding ways of reconstructing local artistic communities, and a large part of that is mapping.

|

| Artistic communities mapped using Google maps |

I’ve been using Google maps, for instance, to map the locations of parish churches and artists’ addresses and other key sites to get a sense of how people inhabited the early modern city. I’ve been building up a rich picture of the demographies and geographies of 18th-century artistic communities in Paris, mapping where these communities were concentrated, and tracing artists’ social networks at the local ‘neighbourhood’ level. (I’m going to be presenting some of this material next week in Paris at the Art & Sociability conference that I mentioned in my last post).

What I kept finding myself wanting, however, was a ‘historical’ Google maps.

|

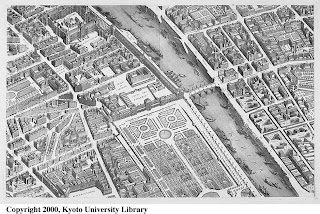

| Plan de Turgot (Source: Kyoto University) |

For an intimate sense of early modern Paris, my favourite map is the Plan de Turgot. It was commissioned by Michel-Étienne Turgot (prévôt des marchands de Paris) in 1734, and completed by Louis Bretez (architect and master of perspective) in 1739. Bretez and his team of map makers went all over the city, into private courtyards and gardens, drawing pictures and taking measurements, to produce a map in isometric perspective with incredible detail of individual streets and residences. All the sections of the map have been digitised by the University of Kyoto and are available online.

But the urban structure of Paris changed considerably in the 19th century. Baron Haussman’s renovation of the streets of Paris in the 1850s and 1860s dramatically altered the fabric of the city, razing buildings and entire streets to make way for his network of boulevards. For an 18th century-ist, sometimes it’s difficult to imagine what the city was like a hundred years earlier. Before the Louvre had its large symmetrical wings, for example, the area around the palace was made up of little residential streets with shops and churches, and before the quays of Paris became roads, they were functioning ports.

|

| Louvre in 1739 (Source: Kyoto Uni) |

|

| Louvre in 2011 (Source: Googlemaps) |

I’ve spent many hours in Paris wandering around streets with printed bits of Turgot’s map trying to work out where things were… fun but not very effective. It gave me a great sense of the early modern city, but apart from lots of coloured annotations on bits of paper, no way of visualising it.

Bridging that disconnect between the 18th century and today – between Turgot’s Paris and Google’s Paris – became a lot easier a few months ago when Mia Ridge drew my attention to some fantastic sites which I’ve found both useful (as research tools) and inspiring (as visualisations of urban history research).

|

| Plan de Turgot over Google maps using Georeferencer |

One was Georeferencer – a georeferencing tool that is solving exactly that disconnect by allowing the comparison of old maps with modern. Using three or more geographic reference points that haven’t changed between the 18th century and today, I was able to overlay Turgot’s 1739 map and Google maps and ended up with this. Now I could work out much more quickly where certain 18th-century streets were in relation to modern streets, and how and where the city has changed most significantly.

|

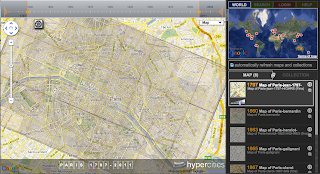

| Paris in 1797 superimposed over Paris today (Hypercities) |

Another fantastic site was Hypercities, where all this overlaying is already done for you using historical maps in excellent resolution. They have maps for many cities all over the world, including Berlin, Lima, London, New York, Saigon, Tehran, Tel Aviv and Tokyo. Beyond the extensive geographic coverage, there are two things that make Hypercities so useful. First is the historical coverage: each city has several maps (for Paris there are maps from 1705, 1797, 1860, 1863, 1865, 1867, 1900, 1920) so you can get a sense of how the city is changing at different points, and when major expansions occur. Second, and probably most useful, is the opacity function, which allows you do make the historical map more or less transparent so that Googlemaps (or the satellite view) is easier to see underneath. As you move the opacity slider, it really feels like you’re zooming between two centuries.

And if you’re imagining how great it would be to have this on a mobile device with GPS, so you could wander quite literally through the streets of the past, then look no further than Look Back Maps, who have developed an iPhone app which locates historical data on contemporary maps (video demo). Another similar technological activation of historical geographies and archives is Philaplace, a local urban history project of Philadelphia using maps, photos and other data, which I’ve already blogged about here.

Maybe it’s not so cold afterall…

I was shivering looking at the snow outside in Oxford and wondering (as I often do) how they coped in the 18thC without central heating and double glazing…

And then I did a little googling and realised I had nothing at all to complain about. Who knew it was so much colder in the 18thC!

According to the Central England Temperature (CET) record, the coldest year ever was 1740 (with a very mean mean temperature of 6.84C), the coldest ever month was January 1795 (with a mean temperature of -3.1C), and the coldest winter was 1684 (with a mean temperature from Dec-Feb of -1.17C). The 18thC even boasts the record for the coldest summer, which was in 1725 (with a mean temperature of 13.1C).

The last days of 2010 feel practically balmy now…