Posts in Category: Paris

Academic Culture & Competition in Early Modern Europe

This year’s Early Modern Research Centre colloquium at the University of Reading is on the culture of competition in Europe’s Academies. I will be giving a paper on the culture of institutional competition that drove artistic production in 17th-century Paris (a short abstract follows below), which is drawn from my book, Académie Royale: A History in Portraits (due out next year).

| http://www.reading.ac.uk/emrc/events/emrc-events.aspx |

St-Jean-de-Montmartre: a modernist church in Paris

This is somewhat beyond my usual ’18e siècle’ parameters but it is in Paris, it is about the history of the church, and it is in the ’18e arrondissement’ so I think we’re ok. On a recent trip to Paris I came across this remarkable church from the turn of the century. I know very little about it other than what the guidebooks say, namely that it was built between 1894 and 1904, designed by Anatole de Baudot (student of Viollet-le-Duc and Henri Labrouste), and is most notable for being the first example of reinforced cement in church construction.

Perhaps I’ve been looking at 17th/18th-century architecture for too long, but I found the use of materials in the interior and exterior wonderfully striking, from the Art Nouveau brick and ceramic tile facade, to the bare cement interior walls beautifully picking up light from the stained glass windows. I’m not sure that my photos do it justice, but it is well worth a detour to explore some of the finer details (like the iron and cement font) and to experience the cavernous space of the nave. If railway stations of the late 19th-century were modelled on medieval cathedrals, then this church brings us full circle, re-appropriating the railway aesthetic to construct a thoroughly modern church that nods politely at Gothic revival. Just look at the clock on the gallery in front of the organ – it makes you feel like you’re about to miss a train! The chandeliers are also marvellous and I cannot imagine cement and metal doing a better job at enacting vaulting or arches.

St-Jean-de-Montmartre is on rue des Abbesses in the 18e, just across the road from Metro Abbesses.

Hacking Historical Maps… or trying to

This weekend, I spent Sunday afternoon experimenting with solutions for historical mapping with Mia Ridge, a digital humanist and doyenne of hack days. We staged our own mini hack day to work through some of the challenges involved with the mapping side of my project on Parisian parishes, a major component of which involves geolocating demographic data to map the neighbourhoods in which artists lived in 18th-century Paris.

Over the past few years I’ve done the archival digging to come up with the data and now I’m at the stage of looking for the best ways to visualise it, both for research purposes (i.e. for me to use while thinking through and writing up the results) and for publication (i.e. how do you get copyright to publish a map in a book or journal article when you’ve built it on a commercial service like Google Maps?). Today we were mainly focusing on the first problem as it seemed the easier of the two, but ideally there’ll be a single solution for both.

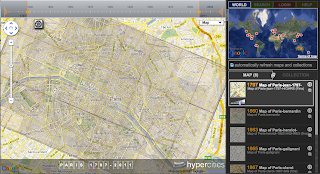

I experimented with two websites, Georeferencer and Hypercities, both of which I’ve used in the past, but today I was hoping to explore some more of their features. In the end, however, while both have some useful functionalities, neither was perfectly suited to my requirements (though it must be said that Hypercities seemed to have a bug that was preventing data from being saved so it was difficult to explore far). As you can see from the screenshot of my results with Georeferencer, I successfully georeferenced a fragment of an 18th-century map on Google Maps… but there was no way to geolocate historical data on it.

Mia experimented with Metacarter and Mapwarper, and has written up her results and experiences over at Open Objects. I have a major problem with sites like Metacarter because everything you produce is publicly visible, which obviously makes it very difficult when you’re working with unpublished data. Most sites allow the option of keeping the maps you make restricted and that makes more sense for academics using these sites for research purposes. I’m excited to share my research when it’s complete, but I’d like to have control over what happens in the meantime.

| Administrative map of Paris, 1890 (Uni of Chicago Library) |

So all-in-all I didn’t discover the ideal open-access resource in a single afternoon (shock-horror) and for now I’ll just have to keep going with the methods I’ve been using. But I have been able to pinpoint more accurately what it is that I’m looking for and what challenges I face in finding it. And as a happy bi-product we also discovered lots of wonderful sites providing access to historical maps that I hadn’t encountered before, like the David Rumsey Map Collection and a great collection of 19th-century maps of Paris at the University of Chicago Library (most in high resolution with zoomify for getting into the detail of street level, as you can see in the screenshot).

A Fête-Dieu Procession in Paris: Now and Then

This is a photo from a Fête-Dieu procession that I took when I was in Paris in June this year. As part of my research on eighteenth-century religious art in Parisian parishes, I’ve been looking into the history of these processions during the early modern period and so was keen to get some sense of the experience even at this historical remove. The traditionalist parish of Saint-Nicolas-du-Chardonnet is now one of the only parishes left in the city that still performs the ritual.

Fête-Dieu (or Corpus Christi) is a moveable feast of the Roman Catholic Church (and some other Christian churches) celebrated annually in the week after Trinity Sunday (usually falling in May or June). The feast originated as a practice in the thirteenth century, and liturgically it commemorates the ritual of the Eucharist.

By the eighteenth-century, however, the feast day was not only theologically significant, but had also become a key community event in the urban calendar. One of the key rituals associated with the feast is the procession in which the consecrated Host is carried out of the church and into the streets of the parish so that all the community could witness and celebrate the Body of Christ. Each parish had its own procession in which the clergy and congregation would walk through and around the parish, marking its boundaries, and thus celebrating (or at least demarcating) the spaces encompassed by the local community.

|

| Place Dauphine on Turgot’s 1739 map of Paris |

Fête-Dieu holds significance for art historians of eighteenth-century France because of the material and visual impact of these processions. During this feast, the church was, to a certain extent, turned inside out, as the streets were decorated with banners and paintings to honour the passing Host. Moreover, until the Académie’s Salon exhibitions were inaugurated in 1737, Fête-Dieu was also the occasion for the city’s only public art exhibition at Place Dauphine, an annual display where artists exhibited their works outside in the square (seen here on Turgot’s map at the end of what is now the Île de la Cité).

|

| Contemporary Fête-Dieu Procession route (base map from Google) |

As I said at the start, Saint-Nicolas-du-Chardonnet is now the only parish in Paris that still celebrates the feast. I was expecting the route of the procession to mark out the parish boundaries as it did in the eighteenth century, but it seems the procession is no longer a strictly local event. As you can see from the route that I mapped as we walked (left), the Saint-Nicolas-du-Chardonnet procession is far from confined to the 5th arrondissement. It begins at the church, but then makes its way to the Seine, crossing onto the Île de la Cité and then onto the Right Bank. Proceeding along the Quai de l’Hôtel de Ville, it then crosses back onto the Île Saint Louis, stopping briefly at a temporary altar on the Pont de la Tournelle where the host is elevated (with the Cathedral of Notre-Dame as a backdrop – as you can see in the photo below), before the procession moves back into the 5th arrondissement and returns to the church. With hundreds of participants walking and chanting, while altar boys swing incense from thuribles, and little children sprinkle flower petals, the procession, not surprisingly, causes a significant interruption to city life. Stopping traffic as it moves along occupying the full width of streets (for nearly two hours in total), the whole event is controlled by the police with patrol cars and metal barricades strategically placed along the route.

| Temporary altar on procession route with Notre-Dame in the background |

It was fascinating to witness how this medieval ritual has survived and yet how much it has clearly evolved, not just since the Middle Ages, but since the eighteenth-century… from a local community event in which neighbourhoods came together to celebrate… to a city-wide proclamation of traditionalist Roman Catholic belief which most Parisians now seem to greet with impatience.

New Ways through Old Maps: Artistic Communities in 18th-Century Paris

As part of my research on 18th-century French religious art, I’ve been doing significant archival work on artists and parish life in Paris. A large part of this involves finding ways of reconstructing local artistic communities, and a large part of that is mapping.

|

| Artistic communities mapped using Google maps |

I’ve been using Google maps, for instance, to map the locations of parish churches and artists’ addresses and other key sites to get a sense of how people inhabited the early modern city. I’ve been building up a rich picture of the demographies and geographies of 18th-century artistic communities in Paris, mapping where these communities were concentrated, and tracing artists’ social networks at the local ‘neighbourhood’ level. (I’m going to be presenting some of this material next week in Paris at the Art & Sociability conference that I mentioned in my last post).

What I kept finding myself wanting, however, was a ‘historical’ Google maps.

|

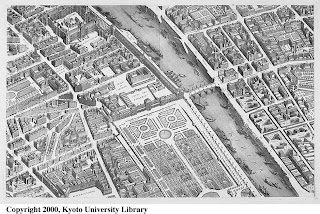

| Plan de Turgot (Source: Kyoto University) |

For an intimate sense of early modern Paris, my favourite map is the Plan de Turgot. It was commissioned by Michel-Étienne Turgot (prévôt des marchands de Paris) in 1734, and completed by Louis Bretez (architect and master of perspective) in 1739. Bretez and his team of map makers went all over the city, into private courtyards and gardens, drawing pictures and taking measurements, to produce a map in isometric perspective with incredible detail of individual streets and residences. All the sections of the map have been digitised by the University of Kyoto and are available online.

But the urban structure of Paris changed considerably in the 19th century. Baron Haussman’s renovation of the streets of Paris in the 1850s and 1860s dramatically altered the fabric of the city, razing buildings and entire streets to make way for his network of boulevards. For an 18th century-ist, sometimes it’s difficult to imagine what the city was like a hundred years earlier. Before the Louvre had its large symmetrical wings, for example, the area around the palace was made up of little residential streets with shops and churches, and before the quays of Paris became roads, they were functioning ports.

|

| Louvre in 1739 (Source: Kyoto Uni) |

|

| Louvre in 2011 (Source: Googlemaps) |

I’ve spent many hours in Paris wandering around streets with printed bits of Turgot’s map trying to work out where things were… fun but not very effective. It gave me a great sense of the early modern city, but apart from lots of coloured annotations on bits of paper, no way of visualising it.

Bridging that disconnect between the 18th century and today – between Turgot’s Paris and Google’s Paris – became a lot easier a few months ago when Mia Ridge drew my attention to some fantastic sites which I’ve found both useful (as research tools) and inspiring (as visualisations of urban history research).

|

| Plan de Turgot over Google maps using Georeferencer |

One was Georeferencer – a georeferencing tool that is solving exactly that disconnect by allowing the comparison of old maps with modern. Using three or more geographic reference points that haven’t changed between the 18th century and today, I was able to overlay Turgot’s 1739 map and Google maps and ended up with this. Now I could work out much more quickly where certain 18th-century streets were in relation to modern streets, and how and where the city has changed most significantly.

|

| Paris in 1797 superimposed over Paris today (Hypercities) |

Another fantastic site was Hypercities, where all this overlaying is already done for you using historical maps in excellent resolution. They have maps for many cities all over the world, including Berlin, Lima, London, New York, Saigon, Tehran, Tel Aviv and Tokyo. Beyond the extensive geographic coverage, there are two things that make Hypercities so useful. First is the historical coverage: each city has several maps (for Paris there are maps from 1705, 1797, 1860, 1863, 1865, 1867, 1900, 1920) so you can get a sense of how the city is changing at different points, and when major expansions occur. Second, and probably most useful, is the opacity function, which allows you do make the historical map more or less transparent so that Googlemaps (or the satellite view) is easier to see underneath. As you move the opacity slider, it really feels like you’re zooming between two centuries.

And if you’re imagining how great it would be to have this on a mobile device with GPS, so you could wander quite literally through the streets of the past, then look no further than Look Back Maps, who have developed an iPhone app which locates historical data on contemporary maps (video demo). Another similar technological activation of historical geographies and archives is Philaplace, a local urban history project of Philadelphia using maps, photos and other data, which I’ve already blogged about here.

Streets of Paris & Virtual Locations of History

By contrast, one of the most successful and engaging online local history projects I’ve come across recently is about the streets of Philadelphia rather than the streets of Paris… the interactive website PhilaPlace, made by the Historical Society of Philadelphia.

|

| PhilaPlace |

Using images, text, video, audio and historical maps, the site connects history and place at a local level, or as they put it: “PhilaPlace weaves stories shared by ordinary people of all backgrounds with historical records to present an interpretive picture of the rich history, culture, and architecture of our neighborhoods, past and present.”

|

| Tour on PhilaPlace |

Navigating your way around town using historical maps, you feel like you’re exploring the city both geographically and through layers of time. You can move through the past by selecting different maps – from the contemporary Googlemap, to earlier ones from 1962, 1935, 1895 and 1875 – giving an impression of the changing size and structure of the urban environment. All of these maps are pinned with the same points of interest – including churches, historical buildings, well-known businesses and cemeteries – offering a sense of the history of these urban spaces, and the shifts and continuities in the communities that have lived there. Each place has a description and several images from different moments (black & white or colour depending on the period), showing either the building, street views, or images of Philadelphians using the place. You can filter the points of interest to show specific themes (e.g. ‘health’, ‘immigration’, or ‘religious life’), and if you can’t decide how to wander the streets yourself, you can take a guided tour! (only two at the moment, but presumably more are coming).

I’ve never actually been to Philadelphia, but I have a more intimate sense of its local history now than I do of many places I have visited. In a way, it’s like a 21st-century version of Richard Cobb’s wonderful essay, The Streets of Paris (1980)… using word and image to capture the history of place… but doing it interactively. Now if we could just do this for Paris…

The last jube in Paris

No, not the sweet. I’m talking about architectural jubes, what the French call a jubé and what is better known in English as a rood screen. This is the architectural element of a church that physically separates the choir from the nave, and hierarchically separates the clergy from the laity during a service. The word comes from the Latin phrase intoned by the celebrant before preaching: “Jube, Domine, Benedicere…”

I’ve just returned from a research trip to Paris, where I visited the church of Saint-Étienne-du-Mont (right next door to the Panthéon in the 5th arrondissement), and witnessed first-hand the last jubé still intact in a Paris church.

It was built around 1530-45 by Antoine Beaucorps. The impression it makes on the space of the church is incredible – this huge mass of stone which seems to lightly twirl itself around a couple of columns. It’s known for its stylistic eclecticism, combining organic Renaissance decorative elements on a much more Gothic structure, something which was presumably attracting the numerous architecture students sitting sketching it from the nave while I was there (though I managed to hide them behind a column when taking the photograph).

Jubés were mostly removed from French churches during the Counter Reformation, following those decrees from the Council of Trent that emphasised the importance of making the Mass accessible to the congregation. The jubé wasn’t actually condemned by the Council, but its removal was interpreted as a way of quite literally breaking down the barrier that separated the people from the sacred actions of the service. If the jubé of Saint-Étienne-du-Mont is anything to go by, then all I can say is: what a pity!