Posts By Hannah Williams

New Ways through Old Maps: Artistic Communities in 18th-Century Paris

As part of my research on 18th-century French religious art, I’ve been doing significant archival work on artists and parish life in Paris. A large part of this involves finding ways of reconstructing local artistic communities, and a large part of that is mapping.

|

| Artistic communities mapped using Google maps |

I’ve been using Google maps, for instance, to map the locations of parish churches and artists’ addresses and other key sites to get a sense of how people inhabited the early modern city. I’ve been building up a rich picture of the demographies and geographies of 18th-century artistic communities in Paris, mapping where these communities were concentrated, and tracing artists’ social networks at the local ‘neighbourhood’ level. (I’m going to be presenting some of this material next week in Paris at the Art & Sociability conference that I mentioned in my last post).

What I kept finding myself wanting, however, was a ‘historical’ Google maps.

|

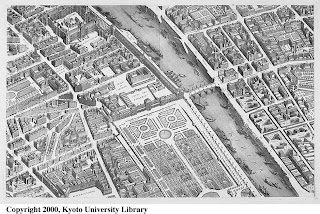

| Plan de Turgot (Source: Kyoto University) |

For an intimate sense of early modern Paris, my favourite map is the Plan de Turgot. It was commissioned by Michel-Étienne Turgot (prévôt des marchands de Paris) in 1734, and completed by Louis Bretez (architect and master of perspective) in 1739. Bretez and his team of map makers went all over the city, into private courtyards and gardens, drawing pictures and taking measurements, to produce a map in isometric perspective with incredible detail of individual streets and residences. All the sections of the map have been digitised by the University of Kyoto and are available online.

But the urban structure of Paris changed considerably in the 19th century. Baron Haussman’s renovation of the streets of Paris in the 1850s and 1860s dramatically altered the fabric of the city, razing buildings and entire streets to make way for his network of boulevards. For an 18th century-ist, sometimes it’s difficult to imagine what the city was like a hundred years earlier. Before the Louvre had its large symmetrical wings, for example, the area around the palace was made up of little residential streets with shops and churches, and before the quays of Paris became roads, they were functioning ports.

|

| Louvre in 1739 (Source: Kyoto Uni) |

|

| Louvre in 2011 (Source: Googlemaps) |

I’ve spent many hours in Paris wandering around streets with printed bits of Turgot’s map trying to work out where things were… fun but not very effective. It gave me a great sense of the early modern city, but apart from lots of coloured annotations on bits of paper, no way of visualising it.

Bridging that disconnect between the 18th century and today – between Turgot’s Paris and Google’s Paris – became a lot easier a few months ago when Mia Ridge drew my attention to some fantastic sites which I’ve found both useful (as research tools) and inspiring (as visualisations of urban history research).

|

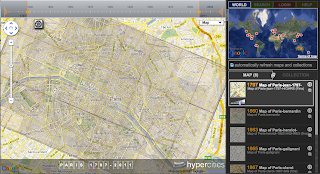

| Plan de Turgot over Google maps using Georeferencer |

One was Georeferencer – a georeferencing tool that is solving exactly that disconnect by allowing the comparison of old maps with modern. Using three or more geographic reference points that haven’t changed between the 18th century and today, I was able to overlay Turgot’s 1739 map and Google maps and ended up with this. Now I could work out much more quickly where certain 18th-century streets were in relation to modern streets, and how and where the city has changed most significantly.

|

| Paris in 1797 superimposed over Paris today (Hypercities) |

Another fantastic site was Hypercities, where all this overlaying is already done for you using historical maps in excellent resolution. They have maps for many cities all over the world, including Berlin, Lima, London, New York, Saigon, Tehran, Tel Aviv and Tokyo. Beyond the extensive geographic coverage, there are two things that make Hypercities so useful. First is the historical coverage: each city has several maps (for Paris there are maps from 1705, 1797, 1860, 1863, 1865, 1867, 1900, 1920) so you can get a sense of how the city is changing at different points, and when major expansions occur. Second, and probably most useful, is the opacity function, which allows you do make the historical map more or less transparent so that Googlemaps (or the satellite view) is easier to see underneath. As you move the opacity slider, it really feels like you’re zooming between two centuries.

And if you’re imagining how great it would be to have this on a mobile device with GPS, so you could wander quite literally through the streets of the past, then look no further than Look Back Maps, who have developed an iPhone app which locates historical data on contemporary maps (video demo). Another similar technological activation of historical geographies and archives is Philaplace, a local urban history project of Philadelphia using maps, photos and other data, which I’ve already blogged about here.

AAH 2011 – Round Up of the Annual Conference

Last week, from Thursday 31 March to Saturday 2 April, the art historians of the world converged on the Midlands for AAH 2011, the Association of Art Historians’ Annual Conference, held this year at the University of Warwick near Coventry.

The main venue was the Warwick Art Centre, with plenary sessions held in the main lecture theatre and the book fair held in the Mead Gallery. Coffee breaks, lunches and receptions were also held in the Mead Gallery, giving delegates plenty of time to browse the selections and take advantage of the publishers’ discounts while milling, chatting, and scoffing tea and cupcakes. I’ve brought home lots of catalogues and stocklists and hope to make a purchase before the offers run out.

The main venue was the Warwick Art Centre, with plenary sessions held in the main lecture theatre and the book fair held in the Mead Gallery. Coffee breaks, lunches and receptions were also held in the Mead Gallery, giving delegates plenty of time to browse the selections and take advantage of the publishers’ discounts while milling, chatting, and scoffing tea and cupcakes. I’ve brought home lots of catalogues and stocklists and hope to make a purchase before the offers run out.

Sessions were run in the nearby Social Sciences block (not quite far enough away to get lost) in well-equipped seminar rooms (though some were a touch on the small side). All the session rooms were close together, which made it relatively easy to slip between sessions without causing too much confusion or disruption. I spent most of my time zipping between sessions on Ephemera (convened by Katie Scott and Richard Taws), Wax (convened by Hanneke Grootenboor and Allison Goudie), and Ugliness (convened by Andrei Pop and Mechthild Widrich). I especially enjoyed Mechthild Fend’s paper on wax moulds of skin diseases from the Hôpital Saint-Louis in Paris; Frédérique Desbuissons’ paper on ‘culinary ugliness’ and the use of food metaphors by nineteenth-century French art critics to critique bad painting; Edward Payne’s paper on Jusepe de Ribera’s prints of grotesque heads and body parts; and Alice Barnaby’s paper ‘fast feedback’, on light and ephemeral viewing experiences in nineteenth-century transparencies.

The plenaries this year were: on Thursday, Stephen Bann (Professor of History of Art, University of Bristol) in conversation with Karen Lang (Editor of The Art Bulletin); and on Friday, Pat Rubin (formerly Head of Research at the Courtauld, now Director of IFA at NYU) who spoke on Art History from the Bottom Up (which did indeed involve a lot of bottoms!). A plenary lecture by Horst Bredekamp had been scheduled for the Thursday but was cancelled, and the conversation with Stephen Bann and Karen Lang was a brilliant replacement. I really enjoyed the different formats of the two plenary events; they gave each night a different flavour.

As always, AAH 2011 combined friendly accessibility with intellectual rigour. One of the things I really appreciate about AAH is the format of sessions, with each speaker giving a 30 minute paper followed by 10 minutes of question time. It means that ideas can be properly developed in the presentation and then properly thrashed out in discussion, as well as giving the audience enough time to move between sessions. However, I do think that we could have squeezed an extra paper into each session (4 rather than 3), especially on the Thursday and Saturday, which were only half days. Overall, fantastic work by Matt Lodder and Claire Davies of the AAH and by the organisers from the History of Art department at the University of Warwick.

Looking forward to doing it all again in Milton Keynes at the Open University for AAH 2012!

Streets of Paris & Virtual Locations of History

By contrast, one of the most successful and engaging online local history projects I’ve come across recently is about the streets of Philadelphia rather than the streets of Paris… the interactive website PhilaPlace, made by the Historical Society of Philadelphia.

|

| PhilaPlace |

Using images, text, video, audio and historical maps, the site connects history and place at a local level, or as they put it: “PhilaPlace weaves stories shared by ordinary people of all backgrounds with historical records to present an interpretive picture of the rich history, culture, and architecture of our neighborhoods, past and present.”

|

| Tour on PhilaPlace |

Navigating your way around town using historical maps, you feel like you’re exploring the city both geographically and through layers of time. You can move through the past by selecting different maps – from the contemporary Googlemap, to earlier ones from 1962, 1935, 1895 and 1875 – giving an impression of the changing size and structure of the urban environment. All of these maps are pinned with the same points of interest – including churches, historical buildings, well-known businesses and cemeteries – offering a sense of the history of these urban spaces, and the shifts and continuities in the communities that have lived there. Each place has a description and several images from different moments (black & white or colour depending on the period), showing either the building, street views, or images of Philadelphians using the place. You can filter the points of interest to show specific themes (e.g. ‘health’, ‘immigration’, or ‘religious life’), and if you can’t decide how to wander the streets yourself, you can take a guided tour! (only two at the moment, but presumably more are coming).

I’ve never actually been to Philadelphia, but I have a more intimate sense of its local history now than I do of many places I have visited. In a way, it’s like a 21st-century version of Richard Cobb’s wonderful essay, The Streets of Paris (1980)… using word and image to capture the history of place… but doing it interactively. Now if we could just do this for Paris…

Google Arting About: an art historian’s perspective on Google Art Project

I got talking with some non-art historians one lunchtime this week about Google Art Project and its applications for art historical research. Most of them were quite surprised that I didn’t just think it was a silly toy for amateurs. But really, what’s not to like about making art history feel like play!?

I got talking with some non-art historians one lunchtime this week about Google Art Project and its applications for art historical research. Most of them were quite surprised that I didn’t just think it was a silly toy for amateurs. But really, what’s not to like about making art history feel like play!?

For most people, visiting a museum (especially when overseas) is a tourist experience; for me, it’s usually work, but that doesn’t mean I don’t enjoy it. Research trips are fun but they are still research. So if Google Art is for the most part about giving people the chance to be ‘virtual tourists’, then I don’t see why it doesn’t give me the same chance to be a ‘virtual researcher’.

Not only is it great to be able to visit museum collections that I’ve never had the opportunity of visiting in the flesh, like the Hermitage, but also the resolution of the images makes it a really useful art viewer. There’s just no way you can get that level of detail (particularly brushwork) in most images on the internet (with a few exceptions like the National Gallery’s zoomy viewer). For me, the detail really is the highlight. Art historians are often interested in less obvious details than those that are usually photographed – Google Art means you can zoom on all kinds of weird things, take a screenshot, and throw it into a Powerpoint presentation for your next class or conference paper.

Not only is it great to be able to visit museum collections that I’ve never had the opportunity of visiting in the flesh, like the Hermitage, but also the resolution of the images makes it a really useful art viewer. There’s just no way you can get that level of detail (particularly brushwork) in most images on the internet (with a few exceptions like the National Gallery’s zoomy viewer). For me, the detail really is the highlight. Art historians are often interested in less obvious details than those that are usually photographed – Google Art means you can zoom on all kinds of weird things, take a screenshot, and throw it into a Powerpoint presentation for your next class or conference paper.

Another thing I was particularly excited about was not just ‘visiting’ galleries I’d never been to, but seeing old favourites in new ways… that is, in ways not possible when you’re standing in the room. I’ve been doing some work on François Lemoyne recently, so when I first had a play with Google Art I went straight to Versailles to hunt out the Apotheosis of Hercules that he painted on the ceiling of the Hercules Salon. I’ve spent many hours standing in that room being jostled by hundreds of tourists, straining my neck and nearly falling over backwards to try and see Lemoyne’s painting. And forget photographing it, that’s always a complete blurry and piecemeal disaster.

But here it is on Google Art, in amazing high resolution that allows you to zoom in on the details in a way that would never be possible in real life… while also being situated in its original setting, so you don’t forget how it was supposed to be viewed and experienced. This way I’m able to consider not only its reception, but also its production: I get to experience how the courtiers saw it from the ground, but also to see it with the proximity that Lemoyne did from the scaffolding when he was painting it. (As an aside – the only problem with this at the moment is that only half the ceiling has been photographed… I’m hoping this will be amended in the fullness of time).

But here it is on Google Art, in amazing high resolution that allows you to zoom in on the details in a way that would never be possible in real life… while also being situated in its original setting, so you don’t forget how it was supposed to be viewed and experienced. This way I’m able to consider not only its reception, but also its production: I get to experience how the courtiers saw it from the ground, but also to see it with the proximity that Lemoyne did from the scaffolding when he was painting it. (As an aside – the only problem with this at the moment is that only half the ceiling has been photographed… I’m hoping this will be amended in the fullness of time).

With the Versailles example, once again I can see how it’s going to become a really useful teaching and presentation tool. I can take a screen shot of the room and the floor plan, showing exactly where in the palace the painting is so I can show students and others who haven’t had the chance to see it in situ for themselves. How great will that be for teaching museum studies and curating courses, giving students a virtual experience of the space and the context of its location in the museum all at once? Of course, in this respect, one of the pros is also one of the cons… it may be an art historian’s relief to see the Mona Lisa without crowds of tourists, but it’s certainly not an authentic experience of the object from a museological perspective.

Google Art is not flawless and it’s not free of issues… but for the art historian, it’s fun, useful and exciting. And that’s enough for me.

The last jube in Paris

No, not the sweet. I’m talking about architectural jubes, what the French call a jubé and what is better known in English as a rood screen. This is the architectural element of a church that physically separates the choir from the nave, and hierarchically separates the clergy from the laity during a service. The word comes from the Latin phrase intoned by the celebrant before preaching: “Jube, Domine, Benedicere…”

I’ve just returned from a research trip to Paris, where I visited the church of Saint-Étienne-du-Mont (right next door to the Panthéon in the 5th arrondissement), and witnessed first-hand the last jubé still intact in a Paris church.

It was built around 1530-45 by Antoine Beaucorps. The impression it makes on the space of the church is incredible – this huge mass of stone which seems to lightly twirl itself around a couple of columns. It’s known for its stylistic eclecticism, combining organic Renaissance decorative elements on a much more Gothic structure, something which was presumably attracting the numerous architecture students sitting sketching it from the nave while I was there (though I managed to hide them behind a column when taking the photograph).

Jubés were mostly removed from French churches during the Counter Reformation, following those decrees from the Council of Trent that emphasised the importance of making the Mass accessible to the congregation. The jubé wasn’t actually condemned by the Council, but its removal was interpreted as a way of quite literally breaking down the barrier that separated the people from the sacred actions of the service. If the jubé of Saint-Étienne-du-Mont is anything to go by, then all I can say is: what a pity!

Maybe it’s not so cold afterall…

I was shivering looking at the snow outside in Oxford and wondering (as I often do) how they coped in the 18thC without central heating and double glazing…

And then I did a little googling and realised I had nothing at all to complain about. Who knew it was so much colder in the 18thC!

According to the Central England Temperature (CET) record, the coldest year ever was 1740 (with a very mean mean temperature of 6.84C), the coldest ever month was January 1795 (with a mean temperature of -3.1C), and the coldest winter was 1684 (with a mean temperature from Dec-Feb of -1.17C). The 18thC even boasts the record for the coldest summer, which was in 1725 (with a mean temperature of 13.1C).

The last days of 2010 feel practically balmy now…